landpirate

campervan untilising nomadic traveller

http://www.vice.com/en_uk/read/southend-bullwood-hall-prison-squat-homelessness?utm_source

I Turned a Shuttered Women’s Prison Into a Protest Squat

By Alex King; Photos: Theo McInnes

October 27, 2016

We're driving down a single track road in the Essex countryside. As the houses peter out, we pass signs that read: "No Access to the Public, Official Visitors Only." The woods grow thicker and, as the light dims, it's starting to feel like the last place you'd want to end up on a leisurely Sunday drive.

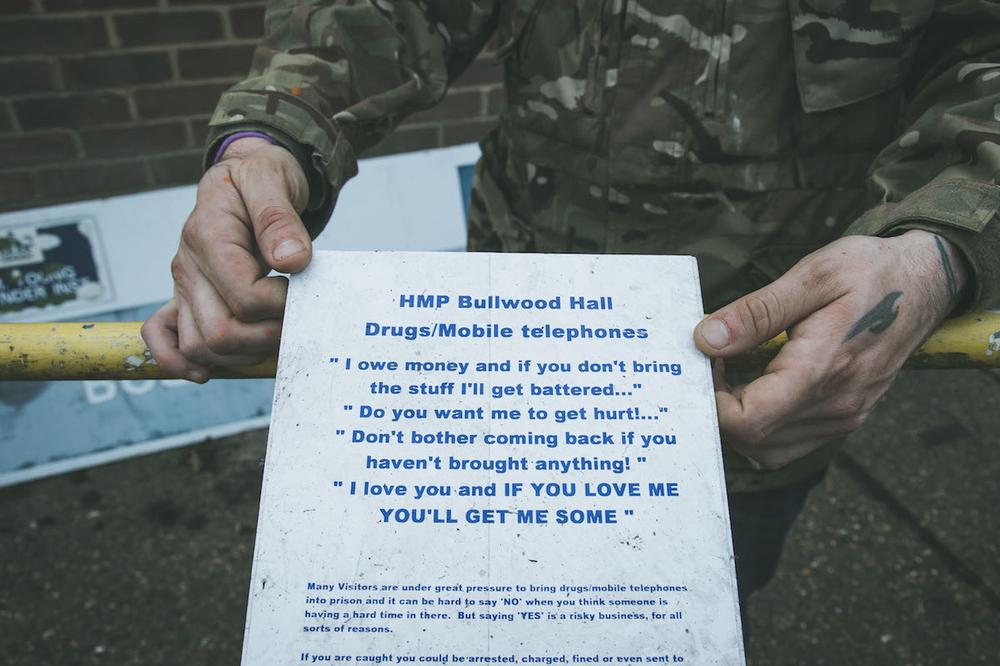

Then we spot a security van parked in front of two huge, grey metal gates topped with razor wire. Until it closed in 2013, this was Her Majesty's Prison Bullwood Hall, a women's prison that also served as a young offenders institute and immigration centre. We pull closer and dogs start barking from inside the van, but the security guard just looks on. The gates swing open from the inside and Darren Davies, the leader of a group of squatters occupying the derelict 48-acre site, stands in an army-surplus camouflage jacket.

"Welcome to my country retreat," he says, beaming and ushering us inside. Darren's a homeless man who's become something of a local celebrity – or menace, depending on who you talk to. He engineered a small-town media shit storm in August when he and his crew occupied the newly vacant BHS building on Southend High Street.

"This is the British Home Stores. I'm British and I deserve a home, so this is my home," he told a reporter from a Southend online TV channel. The Facebook video attracted hundreds of shares and comments, both vilifying and supporting him.

Darren's group have used their string of headline-generating occupations to raise awareness of the area's homelessness problem and highlight the wealth of empty properties that could be used to house them. The prison is their biggest move yet. As Darren walks us through the grounds we're joined by Dan and Tom, both homeless and squatting in the prison.

Dan, left, and Darren, both squatting at HMP Bullwood Hall

Tom, inside the former prison's dorm area

At 19, Dan is the youngest of the group and has been on the streets since February. "I got kicked out of home when I was 16," he says. "It's scary out there." He pulls his sleeve back to reveal two large scabs on his forearm. "This is when I was attacked by a dog. I had to go to hospital and they've only just healed up."

"There was no help I could get," he continues. "I got nowhere on my own – I just kept getting told to go somewhere else. But we all stuck together and look where we are now. This is perfect; I'm not cold at night any more."

We enter the cell block together. It is, quite simply, bleak. I pop my head round into what I'm told was a suicide watch cell. Two doors down, Darren's chosen a cell to make his bedroom. "I'm the only one who's got the bollocks to sleep here," he says, grinning. "As long as no one takes a shit in my cell, I'm all OK." With no power in most of the buildings, the shadows inside are beginning to grow as daylight fades. Getting back into the open air is a relief.

Later, I speak to Mark Flewitt, Southend councillor responsible for housing, for his take on the group's perspective. He says the authority is committed to supporting homeless people and providing necessary services. "Squatting is not a solution to homelessness," he says. "It can hide homelessness, entrench people in unfit accommodation and disconnect vulnerable people from many of the services they would receive if they engaged with the local authority."

But Darren and the others are happy where they are. Tom, 24, credits Darren with getting him off hard drugs. "I could have been housed by now," he says. "But these occupations are more important. We're raising awareness. No one should be homeless, I want everyone off the streets."

Darren proudly shows me the court documents that he says grant the group temporary squatters' rights. "£4.8 million worth of property for 10 pence, not bad," he says – the cost of printing the Section 144 notice stuck to the prison gates, announcing the squatters' claim to the site. "They've labelled me a protester and an activist, but I'm just a homeless man with legal documentation," he continues. "This is me living life the way I want to, and no one else is going to tell me to live it their way."

With his extensive criminal record, Darren knows he's not the cuddly activist people can easily get behind. "I was failed by the care system and have committed a lot of crime from a young age," he says. "I was on benefits for a long time, but I'm not asking for government handouts any more. I ain't stealing this property; they're getting it back eventually. I don't claim it. I'm just borrowing it to put a roof over my head. I may be homeless, but I'm a free living human being and everyone should feel the same way that I should."

Once their court dates arrives, the group is sure to be removed by property owners, Redrow Homes, to make way for the 60 new houses planned for the site – houses they know they won't be able to afford. So what's their next move?

"The coverage we're getting is raising awareness that there's not a lot of help for the homeless," Dan says. "We're gonna keep going bigger and bigger and hope that makes an impact." As Darren opens the gates to let us out, the guard dogs start barking again. "It's all fun and games," he shouts at us as we drive off into the night.

I Turned a Shuttered Women’s Prison Into a Protest Squat

By Alex King; Photos: Theo McInnes

October 27, 2016

We're driving down a single track road in the Essex countryside. As the houses peter out, we pass signs that read: "No Access to the Public, Official Visitors Only." The woods grow thicker and, as the light dims, it's starting to feel like the last place you'd want to end up on a leisurely Sunday drive.

Then we spot a security van parked in front of two huge, grey metal gates topped with razor wire. Until it closed in 2013, this was Her Majesty's Prison Bullwood Hall, a women's prison that also served as a young offenders institute and immigration centre. We pull closer and dogs start barking from inside the van, but the security guard just looks on. The gates swing open from the inside and Darren Davies, the leader of a group of squatters occupying the derelict 48-acre site, stands in an army-surplus camouflage jacket.

"Welcome to my country retreat," he says, beaming and ushering us inside. Darren's a homeless man who's become something of a local celebrity – or menace, depending on who you talk to. He engineered a small-town media shit storm in August when he and his crew occupied the newly vacant BHS building on Southend High Street.

"This is the British Home Stores. I'm British and I deserve a home, so this is my home," he told a reporter from a Southend online TV channel. The Facebook video attracted hundreds of shares and comments, both vilifying and supporting him.

Darren's group have used their string of headline-generating occupations to raise awareness of the area's homelessness problem and highlight the wealth of empty properties that could be used to house them. The prison is their biggest move yet. As Darren walks us through the grounds we're joined by Dan and Tom, both homeless and squatting in the prison.

Dan, left, and Darren, both squatting at HMP Bullwood Hall

Tom, inside the former prison's dorm area

At 19, Dan is the youngest of the group and has been on the streets since February. "I got kicked out of home when I was 16," he says. "It's scary out there." He pulls his sleeve back to reveal two large scabs on his forearm. "This is when I was attacked by a dog. I had to go to hospital and they've only just healed up."

"There was no help I could get," he continues. "I got nowhere on my own – I just kept getting told to go somewhere else. But we all stuck together and look where we are now. This is perfect; I'm not cold at night any more."

We enter the cell block together. It is, quite simply, bleak. I pop my head round into what I'm told was a suicide watch cell. Two doors down, Darren's chosen a cell to make his bedroom. "I'm the only one who's got the bollocks to sleep here," he says, grinning. "As long as no one takes a shit in my cell, I'm all OK." With no power in most of the buildings, the shadows inside are beginning to grow as daylight fades. Getting back into the open air is a relief.

Later, I speak to Mark Flewitt, Southend councillor responsible for housing, for his take on the group's perspective. He says the authority is committed to supporting homeless people and providing necessary services. "Squatting is not a solution to homelessness," he says. "It can hide homelessness, entrench people in unfit accommodation and disconnect vulnerable people from many of the services they would receive if they engaged with the local authority."

But Darren and the others are happy where they are. Tom, 24, credits Darren with getting him off hard drugs. "I could have been housed by now," he says. "But these occupations are more important. We're raising awareness. No one should be homeless, I want everyone off the streets."

Darren proudly shows me the court documents that he says grant the group temporary squatters' rights. "£4.8 million worth of property for 10 pence, not bad," he says – the cost of printing the Section 144 notice stuck to the prison gates, announcing the squatters' claim to the site. "They've labelled me a protester and an activist, but I'm just a homeless man with legal documentation," he continues. "This is me living life the way I want to, and no one else is going to tell me to live it their way."

With his extensive criminal record, Darren knows he's not the cuddly activist people can easily get behind. "I was failed by the care system and have committed a lot of crime from a young age," he says. "I was on benefits for a long time, but I'm not asking for government handouts any more. I ain't stealing this property; they're getting it back eventually. I don't claim it. I'm just borrowing it to put a roof over my head. I may be homeless, but I'm a free living human being and everyone should feel the same way that I should."

Once their court dates arrives, the group is sure to be removed by property owners, Redrow Homes, to make way for the 60 new houses planned for the site – houses they know they won't be able to afford. So what's their next move?

"The coverage we're getting is raising awareness that there's not a lot of help for the homeless," Dan says. "We're gonna keep going bigger and bigger and hope that makes an impact." As Darren opens the gates to let us out, the guard dogs start barking again. "It's all fun and games," he shouts at us as we drive off into the night.