Life on the Road as a Millennial

Ah, life on the open road. So American! Kerouac! Easy Rider! The kid from Into the Wild who ate those seeds and died! Kids are still unplugging and trying out The Hobo Life—but what happens when you add Wi-Fi and Indiegogo campaigns and iPhone apps to the experience? And don't those classic stories of life on the margins seem to end in a sanitarium? Or the grave? Drew Magary joins up with a crew of millennial hobos to find out.

Leaving home was the easy part. I’m at a hobo campground at the dead end of a lonely road at Bastendorff Beach, near the tiny seaside outpost of Charleston in the Great Drifter Heaven that is the state of Oregon. And I couldn’t wait to get here. I left my house on the East Coast, speed-walked impatiently through airports, got a car, and drove four hours, very fast, all to get to this: a parking lot next to a cold-ass beach, where a woman in a shitty sedan with no hubcaps is doing endless doughnuts in the mud and where the surrounding woods host a makeshift tent village for many, many meth addicts.

And yet I was in a hurry, and it wasn’t because I hate my home, or my family. It was just the itch. You know the itch. You wake up every day in a climate-controlled box, then you get into another box to go to work, then you sit in a third box all day just so you can afford bigger boxes and fancy crap to put in those boxes. Somewhere inside all those boxes, you get the itch to blow it all up. Leave everything behind. Live in the motherfuckin’ moment. Like Kerouac did, or Cheryl Strayed, or those people in those Expedia ads.

That’s why I’m here, about to board something called the Vagabus: a broken-down white school bus that a group of cloud-connected 21st-century hobos bought for $1,200 and then adorned with the cutesy Reddit alien logo. My guide through the farthest fringes of THE GRID is the famed Redditor known to all hobos as Huckstah (his real name: Steven Boutwell), who runs the /r/vagabond subreddit and who doles out advice to anyone online who is eager to get away—the bastard son of Bear Grylls and the Pied Piper. In addition to Huckstah, who is 34, we’ve got Ryan, who’s here illegally from Canada (WE NEED A WALL!) and who ditched his job running an IT start-up to live out here. He still dresses like he’s running an IT start-up: nice pants, clean black sweater. There’s Farkus, 27, a bearded mandolin player with faded tats and toenails that haven’t been clipped in months. And there’s Tilly, Farkus’s brunette traveling companion, a mellow Minnesota native who is new to the road and insists, somewhat unconvincingly, that traveling is in her blood.

“It’s not like I’m running away from any problems or anything,” Tilly tells me. “I’m just running away from the fact that I don’t belong staying in one spot, you know? I just got to go.”

Huckstah has a plan to drive the Vagabus all the way down to Argentina, and he would very much like for you to join him. He’s recruiting passengers through the Vagabus website, and he has the life he believes you may secretly want.

But like I said, leaving is the easy part. I came out here to Oregon knowing how it ended for Kerouac (dead from alcohol) and the real-life Dean Moriarty (dead from drugs) and that college kid from Into the Wild (dead inside an old bus…uh-oh). But maybe these kids have cracked the code. It sure seems like there are more of them than ever before, though maybe that’s just because they’re all on Reddit now. Or maybe it’s because the dream is finally REAL. Huck and the gang believe it is. Maybe. But only if you absorb the lessons I did during my one day—and one long, increasingly batshit night—out in the great wide open.

Personal snapshots from Huckstah’s life on the road/rails—that's him below.

You are way more of a pampered baby than you realize. Before I left home, Huck had warned me that nights on the Vagabus can get bitterly cold, and so he recommended a quick pre-stop at Walmart to pick up supplies: a sleeping bag, gloves (fingerless, for the authentic hobo look!), a knit hat, long johns, a big-ass bag of granola, a knife (for picking teeth, whittling, and self-defense), a water bottle, and a pair of wool socks. This, in theory, is all I’d need.

It also dovetailed nicely with my delusional sense of my own spartan lifestyle. I wear the same pair of jeans every day. I drive a Kia.Yessir, I don’t need much to keep me happy!But that’s a hilarious lie. As I was packing, I remembered I needed my phone. Oh, and a charger. And a toothbrush. And what about my ID and credit card? OMG and what about my contact lenses?! Do I sleep with them IN? And do I need some kind of bamboo mat for sleeping on the ground? Pillows! WHAT OF PILLOWS?!

So yeah, pack what you can.

God bless the Jesus freaks and the food banks. When I arrive at the Vagabus around midday, it’s stocked with piles of stale croissants, muffins, doughnuts, and danishes, all scored from a local food bank that had no more mouths to feed. “If no one picks this up, it’s going to a Dumpster,” Huck says. “It’s gold!” A local church group also stopped by earlier today and distributed sandwiches, oranges, and religious pamphlets. One of the oranges was left on a bus seat, with GOD scrawled across it in black marker. Occasionally they also hand out toothbrushes and socks, which are even more prized among hobos than God oranges.

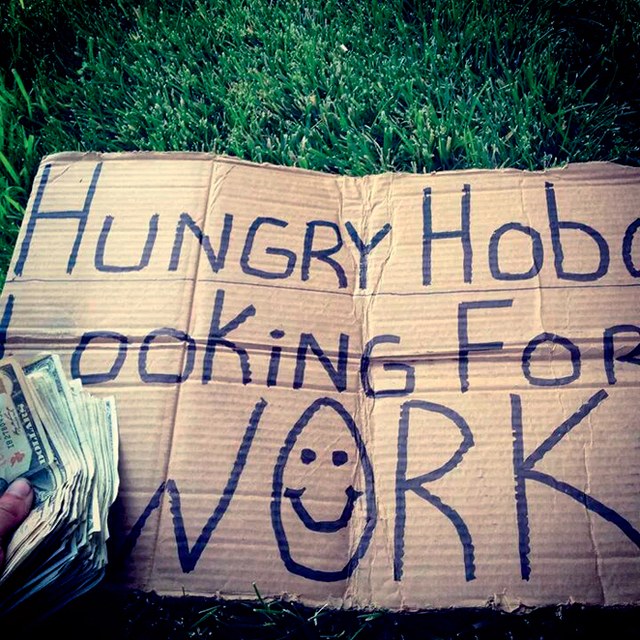

ePanhandle! It takes a lot of gas to get from Oregon to Argentina. So the Vagabus is recruiting riders and raising money through its own Indiegogo page. “We have plans to become a 504(1)(c),” says Huck, directly quoting Kerouac. (By the way, I think he means 501(c)(3).) And even though Huck is dressed in a ratty sweater and has dirt and blood permanently stained into his fingertips, the fact that he’s connected makes him seem different from your average drifter. A phone acts as a signal to others that you are reasonably sane. You are someone with business to tend to.

You will smell. Everyone you meet will smell. “Have you smelled me?” Huck asks.

“No,” I answer. “Should I?”

“I haven’t taken a shower in 60, 70 days,” he reports. “Deodorant is the biggest hoax, dude.”

If you do feel the need to bathe—and plenty of hobos do—Trevor suggests stopping by a Pilot Flying J and asking a trucker to buy you a shower. The showers cost $12. For that much money, though, the trucker may insist on joining you.

Life aboard the Vagabus, back when it was still clutchless and stuck on a tweaker beach in coastal Oregon.

Know the hierarchy of fast-food Wi-Fi hot spots. Out on the road, the “dirty kids” (Huck’s preferred coinage) charge their shit at any one of the many familiar chain joints for quality Wi-Fi squatting. The best of them, shockingly, is Burger King. Compared with McDonald’s, which gives you the evil eye as you milk the clock with free refills and two hours between dollar purchases (“I am ordering food,” says Huck, “just slowly and annoyingly”), BK is a bit more tolerant of vagrants, and it has better Wi-Fi. “I did a speed test with McDonald’s versus Burger King, and Burger King’s was seven times faster!” he says.

You can learn anything using YouTube! Is your car busted? YOUTUBE. Don’t know how to shape an arrowhead? YOUTUBE. Near the Vagabus is another school bus, a black one, belonging to Trevor (not his real name), who tells me he’s an Iraq War vet and who grew so disgusted with suburbia that he packed up his wife and two children and left his Vegas-bodyguard job behind. They’ve been on the road ever since. “I changed my fuel pump after watching a seven-minute video, with $40 worth of returnable tools from Walmart,” Trevor tells me. “You can really just do anything. I also flint-knap.” I don’t even know what flint-knapping is, but now I want to learn. YOUTUBE!

Make bank by foraging for mushrooms. This is Oregon, which would be a lovely state if you could ever see five feet past your face. But thanks to the fog and the Wet-Nap climate, a huge variety of fungi thrive: morels, chanterelles, porcini, and king boletes, which grow right around here. “If you find a really perfect specimen,” says Ryan, “it could be worth $30 for a mushroom.”

Beer, weed, and cigarettes get their own budget. Before anyone makes it to Argentina, there’s the little matter of the bus already being broken down. The clutch is shot; it’ll take hundreds of dollars to fix. But the piggy bank keeps getting raided to buy more beer, weed, and loose tobacco.

Huck keeps talking about “getting the fuck out of this parking lot, and we need a clutch to do that.” But he seems unwilling to confront the zero-sum reality here. Apparently the clutch fund is available to raid on an as-needed basis. Petty cash is to be spent on getting drunk and stoned. Because out here, that’s baseline sobriety. It’s at the top of the Hobo Pyramid of Needs.

The moments of bliss are real. As dusk settles in, we head to the beach to gather driftwood, strolling past thick clumps of bull kelp and a dead seal buried in the sand. We find some dry tinder and some damp logs, troop back to the lot, and PRESTO: a genuine hobo campfire.

Once the fire is roaring, we circle around and drink some beer and pass a bowl of weed and cook hot dogs on sticks (mmm…ashy), and Farkus and Tilly bust out their instruments to play some Pogues and “Smoke Along the Track” by Stonewall Jackson. It’s beautiful. Both these kids can sing their butts off.

And here it is: the hobo dream. Right at this moment, you can lie down on the floor of the forest and breathe it all in. No one really knows, or cares, where we are. We have nothing to do, nowhere to be. We have fire. We have music. We have beer and weed. What more could anyone want?

And now that we’re all drunk and high and friends and shit, I get the next-level tips:

Try not to jump moving boxcars. That’s a good way to wind up with a crushed femur. Instead, the safer method is to case out a train yard, learn the schedule for crew changes, and then sneak onto a stopped train, into one of the often unmanned engines at the back, known as a distributed power unit, or DPU. (“If you’re capable of climbing up a ladder,” Huck says, “you can hop trains.”) DPUs often have leather chairs, a fridge, and a bathroom.

Once you learn crew-change schedules, you can trade them with other hobos for goods and services. But never, ever post the schedules online because…

Violating the hobo code will get your ass kicked. For all their hippie rep, hobos are plenty comfortable with street justice. Huck says when he found out that another hobo was posting crew changes and charging tourists money to go on rail-hopping tours, he put a “green light” on him.

What does “green light” mean?

“That just means you’re going to get your ass beat. He’s just taking yuppies out on tourism, and that’s blowing it up for people like us who hop trains to actually use this shit. So he’s green-lighted, and he will run into a bad time. If he ends up in Roseville Yard or fucking Colton Yard or something like that, he doesn’t want to camp too long.”

And now I’m concerned that disclosing this to you will get me green-lighted. Do they green-light people for talking about green-lighting? Fuck.

The bliss never lasts, and when it ends, it ends ugly. It’s dark now, and suddenly from across the parking lot, we hear screaming. And cursing. Suddenly I remember we are not alone out here.

Trevor’s two daughters come running to our campfire.

“My dad needs help!” one of them cries.

We all scramble up from the fire and hustle across the lot, where Trevor is helping out a man named Harry, who is nursing a giant gash above his eye. Harry explains how he was attacked by another drifter camped out nearby: a man named Richard, whom everyone out here knows and everyone out here tries to avoid.

“He was kicking me while I was on the ground,” Harry says, rambling. “He knows I don’t have a pancreas.” In the firelight, I can see Harry’s gash open and oozing. I ask him if he wants to go to a hospital. “I should,” Harry answers. “But I won’t. I want the cops to come and arrest his ass. Violence.”

If we got a cab to drop you off without any police interference—would you want that?

“No. I just want his ass arrested. I’ve outlived death three times. I’ve actually talked to Christ twice. I’ve been to heaven three times. This son of a bitch over here… He took a rock from his goddamn campfire, came after me like a mad dog and kicked the fucking living shit out of me.”

About 20 yards away, Richard is ranting and raving by his campfire. He’s wearing a straw hat and brandishing a very large walking stick. He also seems to have an inexhaustible capacity for swearing out loud.

“He shoved me,” Richard yells, “and I fucking dropped the fool. You don’t fucking touch me.”

Is everything okay now?

“Who are you? Do you know me?”

No, sir.

Huck tells Richard I’m a reporter (this does not thrill me), and Richard starts shaking his staff and spitting rhymes:

I’m a fucking righteous man, That’s who I am. I served Lord Jesus because I can. But don’t come into my house and push me over my wood, Or else I’ll drop you like I should!

“Got that one, reporter?” he asks.

Yes, sir.

“Fuckin’ A.”

I back away from Richard and retreat to the wounded Harry, still propped up next to the black school bus, still bleeding. I ask Tilly if the Vagabus has a first-aid kit. “We’ve got Band-Aids,” she answers, a bit absently, leading me back to the bus. She’s not doing this with any kind of urgency. She may be new to the road, but she’s already seen plenty of this.

“This shit just seems to happen constantly,” she says. “Seriously, every time I talk to someone, they’ve just recently gone through something, you know?”

Does this kind of violence shake you?

“Not me, no. I keep my head down. I don’t fucking try to talk too much, you know?”

Rejecting society means also forfeiting many of its support systems. I want to help Harry, but the hobos don’t want the cops around here because they don’t want to get in trouble themselves. “I don’t want to have to go back to court, federal court,” Harry’s companion tells me, “and talk about any more stuff that he’s been involved with.” And they avoid hospitals because they don’t want to be hounded with medical bills—Farkus proudly declares at one point that he’s never paid any of his hospital bills—or deemed physically unfit for lucrative fishing and construction gigs.

Back at the campfire, I ask Huck if we should check on Harry later tonight, or maybe tomorrow morning. Huck has played the wise raconteur so far, but now his voice goes cold: “I have no business with him as of now. I know he’s safe and not bleeding, and he’s on his own. He just got his ass kicked.”

Out here, getting your ass kicked happens. It’s happened to Huck, it just happened to Harry, and if I stay out here long enough, it’ll happen to me. And that’s if we’re lucky. Farkus tells me about his friend Nick Henri, who slit his own throat and wrists while living under a bridge in Montana. (I looked it up online. Henri’s body wasn’t found until more than a month later.) Huck says a friend of his, who went by the name Hobo Whiskey, blew himself up cooking beans inside his tent: “We found his blue jeans with his knife in there, and his knife case was completely melted. Hobo Whiskey probably made 3,000 cans of soup in that tent before; 3,001—burned it down.”

Other 21st-century hoboing essentials not pictured here: smartphone, fingerless gloves, vape pen.

The nights go on forever. It’s only 10 P.M., but it feels so much later. We need more booze because there’s nothing else to do, so Tilly volunteers to do a run. It’s started raining, hard, but she rides an old bike four miles round-trip in the dark to get a box of Franzia. Farkus shits in the woods and comes back wiping off his hand. “I shit on my thumb. Happens every time.”

We pile into the bus and everyone tells dirty jokes into the night, getting drunker on hobo wine and fat cans of Twisted Tea. Huck slips into his sleeping bag and lies there awake. “I like to close my eyes and just listen,” he says dreamily.

The lights go off and I move to the floor, lying between Farkus and Huck, my head resting on a pack. We’re all involuntarily spooning in our wool socks and long johns. Soon Huck is snoring loud, ripping thunderclaps that make it sound like he has glass in his lungs. The wind shakes our rickety bus down to its wheels. Strange noises waft over from the tweaker settlements nearby.

Then, at 2 A.M., Farkus staggers to his feet and pisses on the wall of the bus. Two minutes later, he barfs all over the floor. Huck stirs. “Farkus!” he yells. “I need you to puke off the bus, dude.” But he keeps puking on the floor. I scramble to the front of the bus and try to squeeze into a new spot. Finally Farkus stops, and bafflingly, he and Huck fall back asleep in the mess.

Two hours later, though, I’m jolted awake again by the sound of a woman crying. It’s Tilly. As she slept, the emergency door at the back of the Vagabus swung open and she fell a few feet to the ground. Now she’s lying facedown in the mud, rain pounding down on her.

Tilly?

“I WANT TO GO HOME!”

We help her back into the bus. Somehow she falls back asleep instantly. She probably won’t remember any of this in the morning.

But I will, and that’s when the last ember of romance goes out for good. The itch is gone. This doesn’t feel much like freedom at all. It feels like what it really is: squalor. The kind of squalor that hundreds of thousands of Americans live in every day—the kind of squalor that is not a choice. The kind of desperation that makes all those boxes we live in suddenly seem so roomy and liberating.

You never get where you’re going. In January I get a short e-mail from Huck: “Hey we found out Tilly actually broke her back that night. She has to go in for a CAT scan.”

The Vagabus is still a long way from Argentina. After I left, it took them another full month to replace the clutch. (Though in the meantime they adopted a pack of road dogs, and some local kids came by and painted cute dolphins and pinwheels on one side of the bus.) But let’s say they do make it all the way south of the equator. What happens after they reach paradise? What then?

“Keep on going,” Huck says. “I have no timeline. I’m not stopping.”

https://www.gq.com/story/millennial-hobo-life

Ah, life on the open road. So American! Kerouac! Easy Rider! The kid from Into the Wild who ate those seeds and died! Kids are still unplugging and trying out The Hobo Life—but what happens when you add Wi-Fi and Indiegogo campaigns and iPhone apps to the experience? And don't those classic stories of life on the margins seem to end in a sanitarium? Or the grave? Drew Magary joins up with a crew of millennial hobos to find out.

Leaving home was the easy part. I’m at a hobo campground at the dead end of a lonely road at Bastendorff Beach, near the tiny seaside outpost of Charleston in the Great Drifter Heaven that is the state of Oregon. And I couldn’t wait to get here. I left my house on the East Coast, speed-walked impatiently through airports, got a car, and drove four hours, very fast, all to get to this: a parking lot next to a cold-ass beach, where a woman in a shitty sedan with no hubcaps is doing endless doughnuts in the mud and where the surrounding woods host a makeshift tent village for many, many meth addicts.

And yet I was in a hurry, and it wasn’t because I hate my home, or my family. It was just the itch. You know the itch. You wake up every day in a climate-controlled box, then you get into another box to go to work, then you sit in a third box all day just so you can afford bigger boxes and fancy crap to put in those boxes. Somewhere inside all those boxes, you get the itch to blow it all up. Leave everything behind. Live in the motherfuckin’ moment. Like Kerouac did, or Cheryl Strayed, or those people in those Expedia ads.

That’s why I’m here, about to board something called the Vagabus: a broken-down white school bus that a group of cloud-connected 21st-century hobos bought for $1,200 and then adorned with the cutesy Reddit alien logo. My guide through the farthest fringes of THE GRID is the famed Redditor known to all hobos as Huckstah (his real name: Steven Boutwell), who runs the /r/vagabond subreddit and who doles out advice to anyone online who is eager to get away—the bastard son of Bear Grylls and the Pied Piper. In addition to Huckstah, who is 34, we’ve got Ryan, who’s here illegally from Canada (WE NEED A WALL!) and who ditched his job running an IT start-up to live out here. He still dresses like he’s running an IT start-up: nice pants, clean black sweater. There’s Farkus, 27, a bearded mandolin player with faded tats and toenails that haven’t been clipped in months. And there’s Tilly, Farkus’s brunette traveling companion, a mellow Minnesota native who is new to the road and insists, somewhat unconvincingly, that traveling is in her blood.

“It’s not like I’m running away from any problems or anything,” Tilly tells me. “I’m just running away from the fact that I don’t belong staying in one spot, you know? I just got to go.”

Huckstah has a plan to drive the Vagabus all the way down to Argentina, and he would very much like for you to join him. He’s recruiting passengers through the Vagabus website, and he has the life he believes you may secretly want.

But like I said, leaving is the easy part. I came out here to Oregon knowing how it ended for Kerouac (dead from alcohol) and the real-life Dean Moriarty (dead from drugs) and that college kid from Into the Wild (dead inside an old bus…uh-oh). But maybe these kids have cracked the code. It sure seems like there are more of them than ever before, though maybe that’s just because they’re all on Reddit now. Or maybe it’s because the dream is finally REAL. Huck and the gang believe it is. Maybe. But only if you absorb the lessons I did during my one day—and one long, increasingly batshit night—out in the great wide open.

Personal snapshots from Huckstah’s life on the road/rails—that's him below.

You are way more of a pampered baby than you realize. Before I left home, Huck had warned me that nights on the Vagabus can get bitterly cold, and so he recommended a quick pre-stop at Walmart to pick up supplies: a sleeping bag, gloves (fingerless, for the authentic hobo look!), a knit hat, long johns, a big-ass bag of granola, a knife (for picking teeth, whittling, and self-defense), a water bottle, and a pair of wool socks. This, in theory, is all I’d need.

It also dovetailed nicely with my delusional sense of my own spartan lifestyle. I wear the same pair of jeans every day. I drive a Kia.Yessir, I don’t need much to keep me happy!But that’s a hilarious lie. As I was packing, I remembered I needed my phone. Oh, and a charger. And a toothbrush. And what about my ID and credit card? OMG and what about my contact lenses?! Do I sleep with them IN? And do I need some kind of bamboo mat for sleeping on the ground? Pillows! WHAT OF PILLOWS?!

So yeah, pack what you can.

God bless the Jesus freaks and the food banks. When I arrive at the Vagabus around midday, it’s stocked with piles of stale croissants, muffins, doughnuts, and danishes, all scored from a local food bank that had no more mouths to feed. “If no one picks this up, it’s going to a Dumpster,” Huck says. “It’s gold!” A local church group also stopped by earlier today and distributed sandwiches, oranges, and religious pamphlets. One of the oranges was left on a bus seat, with GOD scrawled across it in black marker. Occasionally they also hand out toothbrushes and socks, which are even more prized among hobos than God oranges.

ePanhandle! It takes a lot of gas to get from Oregon to Argentina. So the Vagabus is recruiting riders and raising money through its own Indiegogo page. “We have plans to become a 504(1)(c),” says Huck, directly quoting Kerouac. (By the way, I think he means 501(c)(3).) And even though Huck is dressed in a ratty sweater and has dirt and blood permanently stained into his fingertips, the fact that he’s connected makes him seem different from your average drifter. A phone acts as a signal to others that you are reasonably sane. You are someone with business to tend to.

You will smell. Everyone you meet will smell. “Have you smelled me?” Huck asks.

“No,” I answer. “Should I?”

“I haven’t taken a shower in 60, 70 days,” he reports. “Deodorant is the biggest hoax, dude.”

If you do feel the need to bathe—and plenty of hobos do—Trevor suggests stopping by a Pilot Flying J and asking a trucker to buy you a shower. The showers cost $12. For that much money, though, the trucker may insist on joining you.

Life aboard the Vagabus, back when it was still clutchless and stuck on a tweaker beach in coastal Oregon.

Know the hierarchy of fast-food Wi-Fi hot spots. Out on the road, the “dirty kids” (Huck’s preferred coinage) charge their shit at any one of the many familiar chain joints for quality Wi-Fi squatting. The best of them, shockingly, is Burger King. Compared with McDonald’s, which gives you the evil eye as you milk the clock with free refills and two hours between dollar purchases (“I am ordering food,” says Huck, “just slowly and annoyingly”), BK is a bit more tolerant of vagrants, and it has better Wi-Fi. “I did a speed test with McDonald’s versus Burger King, and Burger King’s was seven times faster!” he says.

You can learn anything using YouTube! Is your car busted? YOUTUBE. Don’t know how to shape an arrowhead? YOUTUBE. Near the Vagabus is another school bus, a black one, belonging to Trevor (not his real name), who tells me he’s an Iraq War vet and who grew so disgusted with suburbia that he packed up his wife and two children and left his Vegas-bodyguard job behind. They’ve been on the road ever since. “I changed my fuel pump after watching a seven-minute video, with $40 worth of returnable tools from Walmart,” Trevor tells me. “You can really just do anything. I also flint-knap.” I don’t even know what flint-knapping is, but now I want to learn. YOUTUBE!

Make bank by foraging for mushrooms. This is Oregon, which would be a lovely state if you could ever see five feet past your face. But thanks to the fog and the Wet-Nap climate, a huge variety of fungi thrive: morels, chanterelles, porcini, and king boletes, which grow right around here. “If you find a really perfect specimen,” says Ryan, “it could be worth $30 for a mushroom.”

Beer, weed, and cigarettes get their own budget. Before anyone makes it to Argentina, there’s the little matter of the bus already being broken down. The clutch is shot; it’ll take hundreds of dollars to fix. But the piggy bank keeps getting raided to buy more beer, weed, and loose tobacco.

Huck keeps talking about “getting the fuck out of this parking lot, and we need a clutch to do that.” But he seems unwilling to confront the zero-sum reality here. Apparently the clutch fund is available to raid on an as-needed basis. Petty cash is to be spent on getting drunk and stoned. Because out here, that’s baseline sobriety. It’s at the top of the Hobo Pyramid of Needs.

The moments of bliss are real. As dusk settles in, we head to the beach to gather driftwood, strolling past thick clumps of bull kelp and a dead seal buried in the sand. We find some dry tinder and some damp logs, troop back to the lot, and PRESTO: a genuine hobo campfire.

Once the fire is roaring, we circle around and drink some beer and pass a bowl of weed and cook hot dogs on sticks (mmm…ashy), and Farkus and Tilly bust out their instruments to play some Pogues and “Smoke Along the Track” by Stonewall Jackson. It’s beautiful. Both these kids can sing their butts off.

And here it is: the hobo dream. Right at this moment, you can lie down on the floor of the forest and breathe it all in. No one really knows, or cares, where we are. We have nothing to do, nowhere to be. We have fire. We have music. We have beer and weed. What more could anyone want?

And now that we’re all drunk and high and friends and shit, I get the next-level tips:

Try not to jump moving boxcars. That’s a good way to wind up with a crushed femur. Instead, the safer method is to case out a train yard, learn the schedule for crew changes, and then sneak onto a stopped train, into one of the often unmanned engines at the back, known as a distributed power unit, or DPU. (“If you’re capable of climbing up a ladder,” Huck says, “you can hop trains.”) DPUs often have leather chairs, a fridge, and a bathroom.

Once you learn crew-change schedules, you can trade them with other hobos for goods and services. But never, ever post the schedules online because…

Violating the hobo code will get your ass kicked. For all their hippie rep, hobos are plenty comfortable with street justice. Huck says when he found out that another hobo was posting crew changes and charging tourists money to go on rail-hopping tours, he put a “green light” on him.

What does “green light” mean?

“That just means you’re going to get your ass beat. He’s just taking yuppies out on tourism, and that’s blowing it up for people like us who hop trains to actually use this shit. So he’s green-lighted, and he will run into a bad time. If he ends up in Roseville Yard or fucking Colton Yard or something like that, he doesn’t want to camp too long.”

And now I’m concerned that disclosing this to you will get me green-lighted. Do they green-light people for talking about green-lighting? Fuck.

The bliss never lasts, and when it ends, it ends ugly. It’s dark now, and suddenly from across the parking lot, we hear screaming. And cursing. Suddenly I remember we are not alone out here.

Trevor’s two daughters come running to our campfire.

“My dad needs help!” one of them cries.

We all scramble up from the fire and hustle across the lot, where Trevor is helping out a man named Harry, who is nursing a giant gash above his eye. Harry explains how he was attacked by another drifter camped out nearby: a man named Richard, whom everyone out here knows and everyone out here tries to avoid.

“He was kicking me while I was on the ground,” Harry says, rambling. “He knows I don’t have a pancreas.” In the firelight, I can see Harry’s gash open and oozing. I ask him if he wants to go to a hospital. “I should,” Harry answers. “But I won’t. I want the cops to come and arrest his ass. Violence.”

If we got a cab to drop you off without any police interference—would you want that?

“No. I just want his ass arrested. I’ve outlived death three times. I’ve actually talked to Christ twice. I’ve been to heaven three times. This son of a bitch over here… He took a rock from his goddamn campfire, came after me like a mad dog and kicked the fucking living shit out of me.”

About 20 yards away, Richard is ranting and raving by his campfire. He’s wearing a straw hat and brandishing a very large walking stick. He also seems to have an inexhaustible capacity for swearing out loud.

“He shoved me,” Richard yells, “and I fucking dropped the fool. You don’t fucking touch me.”

Is everything okay now?

“Who are you? Do you know me?”

No, sir.

Huck tells Richard I’m a reporter (this does not thrill me), and Richard starts shaking his staff and spitting rhymes:

I’m a fucking righteous man, That’s who I am. I served Lord Jesus because I can. But don’t come into my house and push me over my wood, Or else I’ll drop you like I should!

“Got that one, reporter?” he asks.

Yes, sir.

“Fuckin’ A.”

I back away from Richard and retreat to the wounded Harry, still propped up next to the black school bus, still bleeding. I ask Tilly if the Vagabus has a first-aid kit. “We’ve got Band-Aids,” she answers, a bit absently, leading me back to the bus. She’s not doing this with any kind of urgency. She may be new to the road, but she’s already seen plenty of this.

“This shit just seems to happen constantly,” she says. “Seriously, every time I talk to someone, they’ve just recently gone through something, you know?”

Does this kind of violence shake you?

“Not me, no. I keep my head down. I don’t fucking try to talk too much, you know?”

Rejecting society means also forfeiting many of its support systems. I want to help Harry, but the hobos don’t want the cops around here because they don’t want to get in trouble themselves. “I don’t want to have to go back to court, federal court,” Harry’s companion tells me, “and talk about any more stuff that he’s been involved with.” And they avoid hospitals because they don’t want to be hounded with medical bills—Farkus proudly declares at one point that he’s never paid any of his hospital bills—or deemed physically unfit for lucrative fishing and construction gigs.

Back at the campfire, I ask Huck if we should check on Harry later tonight, or maybe tomorrow morning. Huck has played the wise raconteur so far, but now his voice goes cold: “I have no business with him as of now. I know he’s safe and not bleeding, and he’s on his own. He just got his ass kicked.”

Out here, getting your ass kicked happens. It’s happened to Huck, it just happened to Harry, and if I stay out here long enough, it’ll happen to me. And that’s if we’re lucky. Farkus tells me about his friend Nick Henri, who slit his own throat and wrists while living under a bridge in Montana. (I looked it up online. Henri’s body wasn’t found until more than a month later.) Huck says a friend of his, who went by the name Hobo Whiskey, blew himself up cooking beans inside his tent: “We found his blue jeans with his knife in there, and his knife case was completely melted. Hobo Whiskey probably made 3,000 cans of soup in that tent before; 3,001—burned it down.”

Other 21st-century hoboing essentials not pictured here: smartphone, fingerless gloves, vape pen.

The nights go on forever. It’s only 10 P.M., but it feels so much later. We need more booze because there’s nothing else to do, so Tilly volunteers to do a run. It’s started raining, hard, but she rides an old bike four miles round-trip in the dark to get a box of Franzia. Farkus shits in the woods and comes back wiping off his hand. “I shit on my thumb. Happens every time.”

We pile into the bus and everyone tells dirty jokes into the night, getting drunker on hobo wine and fat cans of Twisted Tea. Huck slips into his sleeping bag and lies there awake. “I like to close my eyes and just listen,” he says dreamily.

The lights go off and I move to the floor, lying between Farkus and Huck, my head resting on a pack. We’re all involuntarily spooning in our wool socks and long johns. Soon Huck is snoring loud, ripping thunderclaps that make it sound like he has glass in his lungs. The wind shakes our rickety bus down to its wheels. Strange noises waft over from the tweaker settlements nearby.

Then, at 2 A.M., Farkus staggers to his feet and pisses on the wall of the bus. Two minutes later, he barfs all over the floor. Huck stirs. “Farkus!” he yells. “I need you to puke off the bus, dude.” But he keeps puking on the floor. I scramble to the front of the bus and try to squeeze into a new spot. Finally Farkus stops, and bafflingly, he and Huck fall back asleep in the mess.

Two hours later, though, I’m jolted awake again by the sound of a woman crying. It’s Tilly. As she slept, the emergency door at the back of the Vagabus swung open and she fell a few feet to the ground. Now she’s lying facedown in the mud, rain pounding down on her.

Tilly?

“I WANT TO GO HOME!”

We help her back into the bus. Somehow she falls back asleep instantly. She probably won’t remember any of this in the morning.

But I will, and that’s when the last ember of romance goes out for good. The itch is gone. This doesn’t feel much like freedom at all. It feels like what it really is: squalor. The kind of squalor that hundreds of thousands of Americans live in every day—the kind of squalor that is not a choice. The kind of desperation that makes all those boxes we live in suddenly seem so roomy and liberating.

You never get where you’re going. In January I get a short e-mail from Huck: “Hey we found out Tilly actually broke her back that night. She has to go in for a CAT scan.”

The Vagabus is still a long way from Argentina. After I left, it took them another full month to replace the clutch. (Though in the meantime they adopted a pack of road dogs, and some local kids came by and painted cute dolphins and pinwheels on one side of the bus.) But let’s say they do make it all the way south of the equator. What happens after they reach paradise? What then?

“Keep on going,” Huck says. “I have no timeline. I’m not stopping.”

https://www.gq.com/story/millennial-hobo-life