The Secret History Of The War On Public Drinking

12/14/2013 07:32 am ET | Updated Jun 26, 2015

AP

New Year's Eve was still three weeks away, but by dusk, crowds had thronged Times Square. Everyone's eyes were trained on the screen on 42nd Street. The buzz of mass anticipation hung in the air. Suddenly, the lights on the screen flickered with the message everyone had been waiting for: "Utah is voting!" A hush fell across the crowd. The "yes" votes from Pennsylvania and Ohio had come in hours earlier, so if Utah voters approved the 21st Amendment as well, liquor would become legal for the first time in the United States in 14 years.

At 5:33 p.m., the screen changed again. "Prohibition is dead!" it declared. Times Square erupted in cheers. The good news rippled out through the city, shouted from the mouths of paperboys and in triumphal booms from the ships in the harbor. That night, all across America, people celebrated by crowding into former speakeasies, hosting raucous parties and drinking in the streets.

Customers buying beer at a makeshift bar in the streets of Chicago, after the legalization of alcohol on Nov. 10, 1933. (Photo by FPG/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

This month, 80 years later, some Americans celebrated the anniversary of the Repeal with old-timey cocktails, good craft beer or at least a festive hashtag (#RepealDay!). But there wasn't much drinking in the streets. Because America is in the grip of a new Prohibition: One that makes it illegal to drink alcohol in public.

Hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of people are arrested or ticketed for drinking in public every year. Millions of others refrain from doing so because they have been conditioned to believe that public drinking is an act as obviously illegal as shoplifting or nude sunbathing in a city park -- even though it was perfectly legal nearly everywhere in the world as recently as 1975.

This Prohibition, unlike the last, isn't the result of a constitutional amendment. Nor did it emerge overnight. The net of laws that now bans public drinking across most of the country took state and city lawmakers 40 years to weave. Most of these laws attracted as little public notice upon their passage as any other state or municipal law, which has allowed this net to be lowered so slowly and quietly that many people don't realize that anything has changed.

Another difference between this Prohibition and the one that ended 80 years ago? Many of the people who are aware of this one actually like it. They say that the virtually nationwide ban on public drinking has "cleaned up the streets," reduced per capita alcohol consumption and even helped slash the incidence of serious crimes such as murder and arson.

They may have a point. But it's also likely that they underestimate the price we pay for the benefits of this Prohibition. Decades of evidence suggest that laws against public drinking are enforced unequally and capriciously, disproportionately hurting the most downtrodden members of society. More fundamentally, these laws allow the state to interfere with individual behavior to prevent an act that in itself harms no one.

AN INTRICATE PATCHWORK

Whether the national prohibition on public drinking is good or bad, it's certainly confusing. Laws against drinking in public places -- streets, sidewalks, parks, beaches, stadiums -- vary wildly from state to state, city to city and in some places, from block to block.

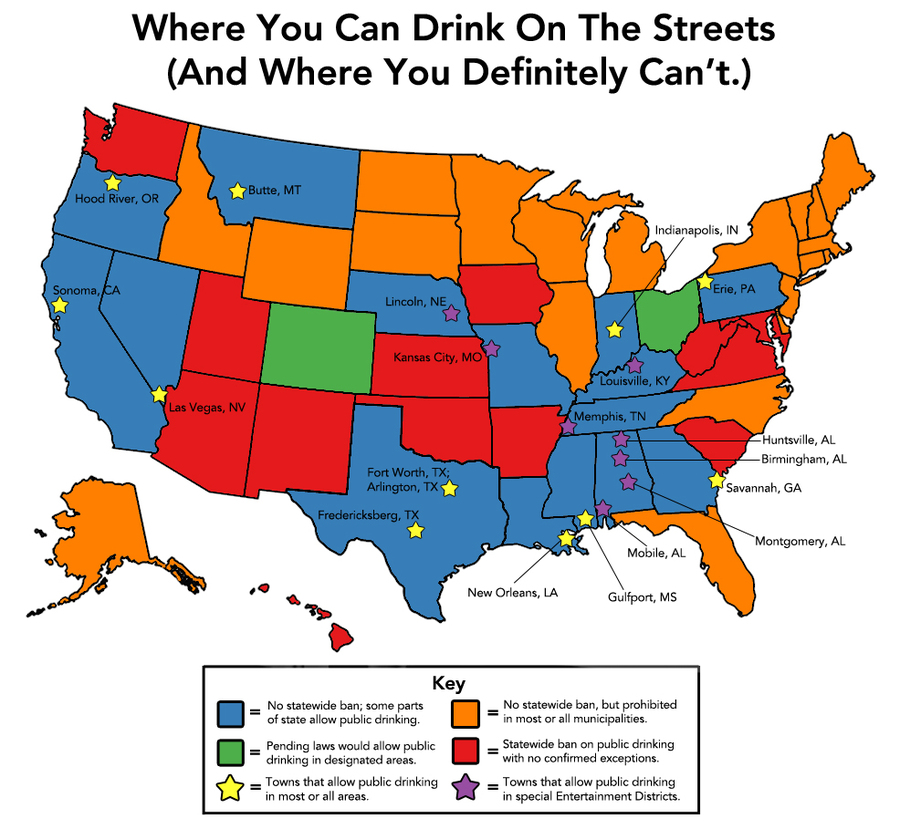

Public drinking is now punishable by fine or jail time across the vast majority of the country. Seventeen states ban it completely. It's also illegal in 89 of the 100 most populous cities in the country, including the top 10. The map below illustrates the bewildering patchwork of public drinking laws currently in effect across the U.S.:

But this map actually masks the true extent of the confusion, because the various municipal and state statutes banning the behavior define the offense in myriad ways. They also stipulate a huge range of penalties for offenders, from a simple fine of $25, payable by mail (New York City), to a ticket of up to $1,000 or a jail sentence of up to 6 months (Hawaii and New Mexico).

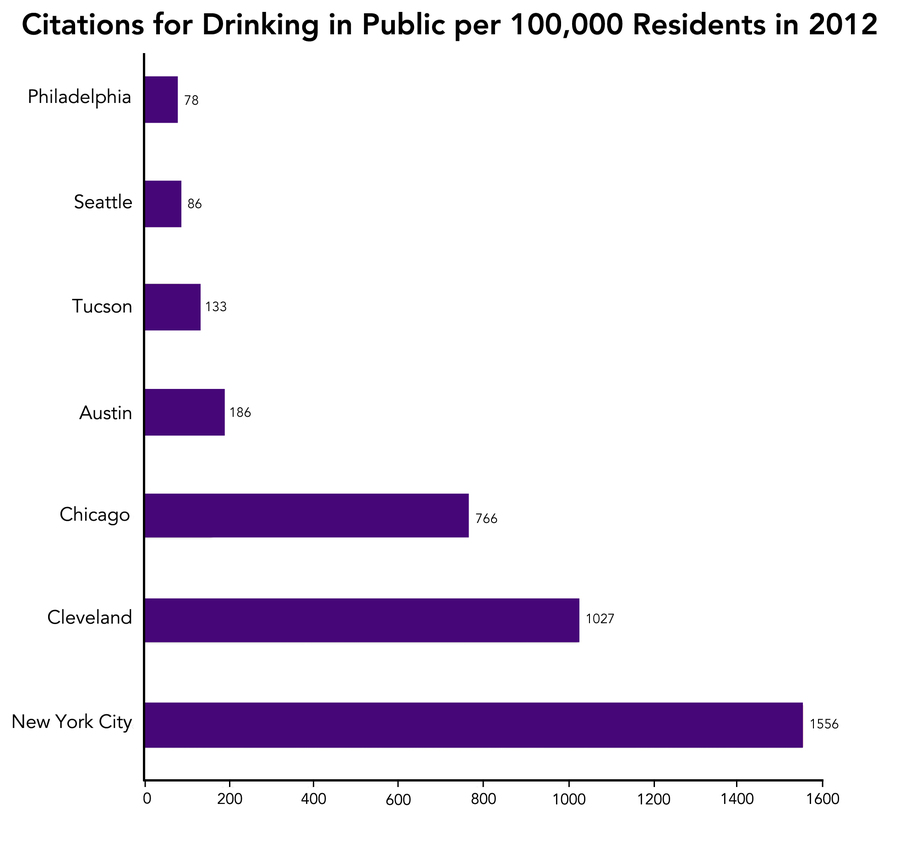

What's more, enforcement of public drinking statutes seems to vary widely from one place to the next. Police departments and municipal courts in several major U.S. cities provided data on enforcement to The Huffington Post, which reveal huge gaps in the arrest rate among comparable cities, as the chart to the right illustrates.

(To some extent, the chart may reflect actual differences in the frequency with which city residents drink in public. For example, people who live in pedestrian-friendly cities like Chicago or New York may have more occasion to drink in public than those who live in cities like Tucson, Ariz., or Austin, Texas. Yet it also seems unlikely that New York City residents drink in public at rate 20 times that of the residents of Philadelphia or Seattle, so differences in how the laws are enforced likely account for the significant disparities.)

HuffPost's analysis could only positively identify 20 towns or cities of any size in which drinking is legal in some, if not all, public places. About half of these cities allow public drinking only in specially designated "Entertainment Districts" that have been established in the past few years in the hopes of attracting booze-loving tourists.

The cities that do allow drinking in public don't have as much in common as one might think. Cities as varied as New Orleans and Butte, Mont., Las Vegas and Savannah, Ga., allow residents and tourists alike to drink in the streets and parks.

But to ask how these places were independently able to legalize public drinking is to fundamentally misunderstand the situation. Towns like New Orleans and Butte didn't have to take specific steps to allow public drinking -- they just never banned it.

About 6 million people -- just under 2 percent of the country -- live in a municipality that allows some measure of public drinking. Even if one rounds up, that leaves 97 percent of Americans facing a ticket or jail time if they step outside their homes while carrying a glass of Chardonnay.

That would have shocked our Founding Fathers -- and even possibly our great-grandfathers. Alcohol has been regulated in North America since at least the earliest days as British colonies. But until the middle of the 20th century, there were exactly two types of American alcohol law: regulations of its sale and bans on public drunkenness. Neither sought to control drinking directly.

Sound legal and philosophical arguments distinguished the laws against the act of drinking from those on the sale of alcohol or public drunkenness. The great legal minds of the 19th Century generally believed that laws should only regulate social activities, or conduct involving multiple parties. The philosopher John Stuart Mill, for example, argued, in his famous essay "On Liberty":

Whenever, in short, there is a definite damage, or a definite risk of damage, either to an individual or to the public, the case is taken out of the province of liberty, and placed in that of morality or law.

But with regard to the merely contingent, or, as it may be called, constructive injury which a person causes to society, by conduct which neither violates any specific duty to the public, nor occasions perceptible hurt to any assignable individual except himself; the inconvenience is one which society can afford to bear, for the sake of the greater good of human freedom.

Anathema to this school of thought are laws that would prevent calm, relatively sober people from drinking wherever they like. So no such laws were passed.

A combination of Victorian social mores and a scarcity of disposable drinking vessels kept most Americans from partaking in their legal right to drink in public too often. But public drinking was certainly a feature of everyday life. Miners and laborers on their lunch hour would pay women and children to bring them buckets of draught beer from local saloons for open-air consumption, a practice known as "rushing the growler."

Oil rig workers in Bayonne, N.J., "rush the growler" on their lunch hour in 1909.

In one newspaper article in 1868, Mark Twain dismissed New England as "the land of steady habits" because he noted so few people drinking and smoking in the streets. And across the country, outdoor festivals for events like New Year's Eve, St. Patrick's Day, major political or military victories and the American centennial always featured alcohol. The relative dearth of written evidence of public drinking may be a sign of how normal it was: Writers may not have thought to comment on it.

It took Prohibition to shatter the assumption that a person could drink with impunity wherever he or she liked.

The Volstead Act, the sweeping 1919 federal law that enforced Prohibition, specifically banned the carrying of containers of alcohol in the street, among other things. The nominal justification for this measure was that carrying wine or bourbon down the street was assumed to be evidence of intent to sell. So the measure was still, at its heart, a regulation of sales. But it effectively confined drinking to speakeasies and private homes.

On the other hand, the repeal of Prohibition 80 years ago gave the states a chance to write wholly new alcohol laws, but they did not use the opportunity to ban public drinking.

Some states essentially restored the legal regime that had been in place prior to 1918. Many others looked to "Toward Liquor Control," a report commissioned by former teetotaler John D. Rockefeller Jr., written by attorney Raymond Fosdick and engineer Albert Scott, that suggested specific laws based on best practices in other countries. Nowhere in the 300 pages of the report do Fosdick and Scott mention the idea of banning the act of drinking in public outright. And the historical record suggests that, for two decades after Prohibition, no one else did, either.

THE BIRTH OF CONTROL

But 20 years and seven days after the repeal of the 18th Amendment, Chicago Alderman Harry L. Sain, who represented the city's 27th Ward, approached his fellow aldermen with a problem.

Shasta Dam construction workers drinking beer at entrance to bar in Central Valley, Calif., c. 1940.

He said he was hearing more and more reports of "bottle gangs" -- groups of indigent men who would stand on sidewalks sharing bottles of liquor -- plaguing the Skid Row of his district, and littering the streets with empty wine bottles and beer cans. Chicago police officers could arrest rowdy individuals using the city's broadly defined ban on "disorderly conduct," but Sain wanted them to be able to break up the bottle gangs before they got rowdy.

His solution? A law that would prohibit "drinking in the public way," namely city streets, parks, vacant lots and any other place open to public view. Violators were subject to a $200 fine, the equivalent of about $1,750 in today's money. On Dec. 12, 1953, the law passed handily. One of Sain's fellow aldermen, Mathias Bowler, told the Chicago Tribune the new law was "good news for [his] ward too," noting that he'd heard that "five fellows die[d] there drinking out of bottles on the street."

If Chicago was the venue where public drinking laws made their debut, Newport, R.I., was where they hit the big time.

Over July 4th weekend 1960, the traditional summer resort for the East Coast elite was the scene of a notorious drunken riot. The town was hosting one of the most important jazz festivals in the country for its sixth summer. But after a popular 1959 documentary about the festival raised the event's profile, 12,000 teens showed up hoping to see Louis Armstrong, Dizzy Gillespie and Dinah Washington perform, only to find it sold out.

While loitering outside the concert, they started drinking. Then they got angry.

About 2,000 of them charged the gates of the festival. Newport police tried to hold them back, but the crowd started throwing beer cans and wine bottles. The police called in the National Guard, which dispersed the crowd with tear gas. It was a disaster.

The following year, Newport regrouped, revising its criminal code to better accommodate the festival. One of the key changes, as the Boston Globe put it, was that a "special ordinance bans drinking in public." The reforms worked, and subsequent festivals went off without a hitch.

The success of the Newport law inspired other towns across the country that were struggling to control large groups of rowdy, drunken teens -- in particular the Florida towns to which college students started flocking for Spring Break after the release of movies like "Gidget" and "Where The Boys Are." Fort Myers, Jacksonville, Miami, Daytona Beach and Hialeah all passed restrictions on public drinking between 1964 and 1970, years before most other towns in America did.

On the whole, though, adoption of public drinking laws was lackadaisical. Until about 1975, such laws were so rare that every newspaper article describing a new one explained it as if it were completely novel. And they might have remained that way forever -- if the Supreme Court hadn't intervened.

DRUNKENNESS DECRIMINALIZED

In 1963, it was unlikely that you would have been arrested for drinking in public -- but you could have been arrested for being a "common drunkard."

Most states and municipalities had laws on the books that made it illegal to be a "common drunkard" or a "vagrant," terms used to describe those who would be known today as alcoholic and homeless, respectively. The police arrested hundreds of thousands of people every year for violating these so-called vagrancy and public drunkenness laws, which were at the heart of the police's mission to control urban social disorder. Such laws defined life on Skid Row: Some perennially homeless, alcoholic men spent years of their lives in jail, in 30-day increments, on charges of public drunkenness and vagrancy.

Two painters sit on a sidewalk during a break, drinking beer and eating sandwiches, c. 1945. (Photo by Harold M. Lambert/Lambert/Getty Images)

But in the late '50s and early '60s, legal scholars started to criticize how these laws were enforced, using arguments that would be familiar to anyone following the contemporary debate around drug decriminalization. Critics argued that arresting, charging and incarcerating "drunkards" wasted scarce police and court resources; that the laws were enforced more stringently against poor black people than against affluent white people; and that "public drunkenness" was a moral and medical issue better addressed in churches and hospitals than jails and courtrooms.

In short, they called for reform. The Supreme Court heeded that call in 1964, in its landmark decision Robinson v. California. The immediate effect of the decision was to strike down a California statute classifying drug addiction as a crime. But it also rang the death knell for all "status offenses," vagrancy chief among them.

In a later decision, the Supreme Court chose not to strike down public drunkenness laws as unconstitutional. The court found that such laws prohibited the act of "appearing in public while drunk," rather than "being an alcoholic."

But the writing was on the wall. Vaguely defined status offenses like public drunkenness and vagrancy were constitutionally unsound and, in the long run, unenforceable.

Further pressure to overturn public drunkenness laws came from the executive and legislative branches. Two Presidential Commissions on Crime described public drunkenness laws as ineffective deterrents to repeat offenders and a burden on the criminal justice system. They strongly recommended that public drunkenness be decriminalized. And in 1971, Congress passed the Uniform Alcoholism Treatment Act, which called on states to decriminalize public drunkenness and shift their handling of public inebriates to the health system. Thirty-five states adopted it, and most of the others passed similar laws.

By the end of the '70s, arrests for public drunkenness had dropped by half nationwide. (They would continue to fall, almost unabated, until the present.) The era of criminalized public drunkenness was over, after 350 years. Doctors and advocates for the rights of the homeless and alcoholics started to breathe easier.

Not everyone was happy, though. Entrenched business interests and well-to-do citizens, and their allies in state and local legislatures, still wanted the police to take undesirable homeless and alcoholic people off the streets. But as public drunkenness and vagrancy were no longer criminal acts, the police had no tools at their disposal.

Enter the ban on public drinking.

CITIES EMBRACE THE NEW PROHIBITION

The idea of implementing a ban on public drinking as a substitute for a ban on public drunkenness isn't as obvious as it might seem.

True, "drinking in public" sounds a lot like "drunk in public" -- so much so that, to this day, many people conflate or confuse the two types of law. While both regulate the overlap of alcoholic beverages and public space, they address fundamentally different behaviors.

A ban on public drunkenness punish the odious outcomes of excessive drinking. It divides the landscape of public social conduct into two large zones -- sober and drunk, good and bad -- and tells people they will be punished if their behavior passes from the sober zone into the drunk zone. It establishes a subjective moral standard for each individual to uphold in his or her own way.

Delivering liquor the day after the repeal of Prohibition, driver Tony Pasquale takes a drink in Manhattan. (Photo By: Ed Jackson/NY Daily News via Getty Images)

Public drinking laws, on the other hand, ban one specific type of action: drinking an alcoholic beverage in a public place. They leave no room for ambiguity or subjectivity. You either are violating the law, or you aren't.

A debate on the merits of these two types of law could raise important ethical and moral questions about police discretion, the impartiality of justice and our basic concept of public space.

But lawmakers and police chiefs made a much simpler calculation when they started to embrace the public drinking law in the wake of decriminalization of drunkenness. Its specificity and lack of ambiguity made it much easier to defend in court than charges of public drunkenness or vagrancy. And it could still be easily used to arrest homeless people and alcoholics. Homeless people often can't afford to drink in bars, and they don't necessarily have a place to drink in private. If they want to drink, they're almost bound to commit the crime of drinking in public.

Between 1975 and 1990, in the wake of the decriminalization of public drunkenness and vagrancy, cities and states gradually imposed bans on drinking in public.

New York City Council voted to ban public drinking just six weeks after public drunkenness was decriminalized throughout New York state on Jan. 1, 1976. Mayor Abraham Beame vetoed the bill, citing its "disturbing civil-liberties implications." Three years later, the council passed another ban, despite vociferous opposition from minority groups -- and Mayor Ed Koch signed it into law.

In May 1983, the Supreme Court struck down California's vagrancy law for being unduly subjective. During the Supreme Court hearing, California Attorney General George Deukmejian said that eliminating the vagrancy law ''effectively removed an arrow from the quiver of the police at a time when all proper weapons are required to deter criminal activity." By August, the City Council was considering a ban on public drinking at the request of the police department. That November, the LAPD got a brand new arrow.

Tim Riggins and Tyra Collette, two of the characters on "Friday Night Lights," enjoy beers in a West Texas field near the fictional town of Dillon.

At some point, though, public drinking bans simply became common enough that even cities without a pressing need for such laws felt pressure to pass them. In 1990, for example, when Irvine, Calif., passed its ban, the city's community services superintendent noted to the LA Times that "You can't consume alcoholic beverages in public" in almost any other city in Orange County, but "you can in Irvine."

The last big holdouts were the Texas giants: Houston, Dallas, San Antonio and Austin. They were prevented from joining in the banning bonanza of the '80s by a state law that prevented cities from passing any law that regulated alcohol consumption. But they clearly felt left out, because they pressured the state to change. They won in 1993.

By 1995, the bulk of the cities in the U.S. had passed bans on public drinking. Since then, these laws have even started to proliferate abroad, especially in the U.K. and Australia. Dublin, Ireland, outlawed public drinking in 2008. Even Prague, long Europe's premier destination for drunken revelry,moved to ban drinking in the streets this fall.

Public drinking bans may be America's most successful culinary export since the Big Mac.

CRIME AND PUNISHMENT

Of course, laws alone do not a Prohibition make. Enforcement must be consistent and harsh enough to make reasonable people believe they're likely to be punished if they break the law. So long as the police used public drinking laws as a tool primarily against homeless alcoholics and mobs of drunken teenagers, the country remained a crucial leap away from an outright Prohibition.

The final piece of the puzzle came during the '90s, as police departments in cities from Seattle to New York began to embrace the "Broken Windows" philosophy of enforcement. The idea holds that strict enforcement of minor "public order" infractions can revive downtrodden neighborhoods, eventually reducing more serious crimes like murder and arson. Advocates of the Broken Windows theory emphasized the enforcement of public drinking laws as early as 1982, when the Atlantic Monthly published the article from which the movement takes its name.

In one pivotal passage, authors George Kelling and James Wilson write:

People start drinking in front of the grocery; in time, an inebriate slumps to the sidewalk and is allowed to sleep it off. Pedestrians are approached by panhandlers. [...] Such an area is vulnerable to criminal invasion. Though it is not inevitable, it is more likely that here, rather than in places where people are confident they can regulate public behavior by informal controls, drugs will change hands, prostitutes will solicit, and cars will be stripped.

Whether or not Kelling and Wilson assume here that public drinking is, strictly speaking, illegal -- it's an open question -- the message is clear: Public drinking is bad for communities. So bad, in fact, that the police should target it specifically as an easy way to reduce rates of more serious crimes.

Which is exactly what police forces did throughout the '90s. Enforcement rates of public drinking laws skyrocketed, inculcating the idea that public drinking is a crime no matter who does it.

Yet patterns of police enforcement of public drinking laws do suggest their origin as a replacement for unacceptably vague and discriminatory status offenses. Though national data on public drinking infractions are hard to come by (or nonexistent), the few studies of police enforcement indicate that poor, black people are arrested at rates many times higher than affluent white people.

Judge Noach Dear of Brooklyn had his staff look into tickets for the offense in his borough in 2012, and found that "More than 85 percent of the 'open container' summonses were given to Blacks and Latinos. Only 4 percent were issued to whites." Nearly 40 percent of Brooklyn residents are white.

In 2001, the City of New Orleans commissioned a study of a then-30-year-old city law that banned open glass and metal (but not plastic) drinking containers on the streets. Researchers found that nearly 80 percent of those charged with violating the open container law were black, prompting the city council to repeal the ban.

That's all to say that anyone can be ticketed for drinking in public under the terms of the new Prohibition. Just as anyone couldbe ticketed or jailed for public drunkenness in 1960. But the available research suggests that young black kids drinking 40s on the corner are more likely to be ticketed than a prosperous, middle-aged white couple drinking a bottle of wine in the park.

A NEW REPEAL MOVEMENT?

The new Prohibition arrived, then, both quickly and slowly. Most cities passed their laws against drinking in public relatively quietly, without much debate in city councils or input from the general public. But the country passed the laws over a long enough span of time that the connection between the old status offenses and the new public drinking bans never became readily apparent to most observers. No one has ever written a scholarly article on the emergence of public drinking laws in America, for example.

The nation certainly seems to have accepted this new Prohibition without resistance.

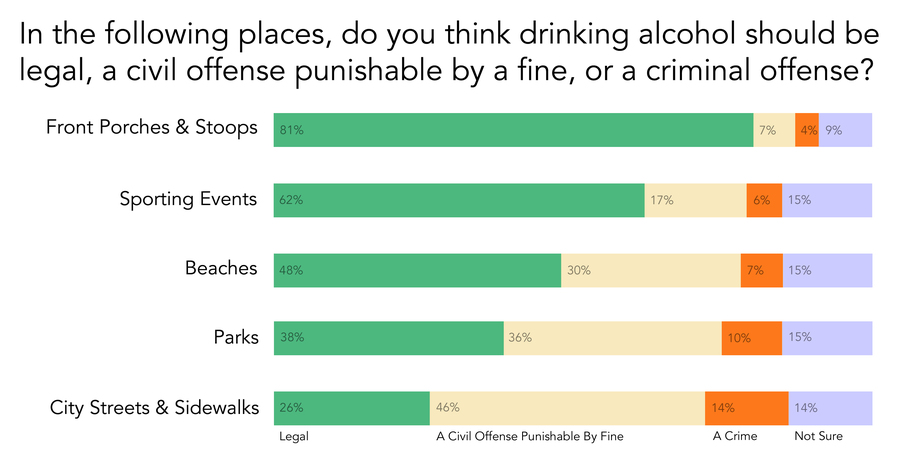

A previous national poll, conducted in 2000 -- and the only one this reporter found on the subject -- indicated overwhelming public support for restrictions on public alcohol consumption: 92 percent of respondents said they favored laws against drinking in the streets and on sidewalks; 86 percent said they favored restrictions on drinking in parks and beaches; and 81.4 percent said they favored restrictions on drinking in stadiums and concerts. Support for public drinking bans in that poll was much higher among older people, women, ethnic minorities and those from low-income households than among young people, men, whites and those from high-income households.

To see whether attitudes had changed in the last 13 years, HuffPost conducted its own poll on the issue with our partners at YouGov. The wording of the questions differed slightly from those of the 2000 poll, and was conducted online rather than over the phone, so the two aren't directly comparable. While HuffPost/YouGov's results revealed many of the same relative differences in support across demographic categories and with regard to specific sites for public drinking, the new poll found much higher levels of support for the legalization of public drinking across the board than the previous poll did.

The infographic below illustrates the top-line results:

The HuffPost/YouGov poll was conducted Dec. 2-3 among 1,000 U.S. adults using a sample selected from YouGov's opt-in online panel to match the demographics and other characteristics of the adult U.S. population. Factors considered include age, race, gender, education, employment, income, marital status, number of children, voter registration, time and location of Internet access, interest in politics, religion and church attendance.

Even in the more recent poll, though, those in favor of restricting street drinking outnumber those in favor of legalization 2-to-1, which is hardly the makings of a latter-day repeal movement.

Some of the ban's popularity may stem from a belief that cracking down on public drinking in the '90s also slashed national crime rates. Police started enforcing public drinking bans aggressively just as rates of serious crime started to plummet in many major cities across the country. Government officials who pushed the Broken Windows theory most forcefully often argued that public drinking arrests have been a crucial factor in that decline. They also note that the city most closely associated with street drinking is New Orleans, which has one of the highest murder rates in the country; while the city most closely associated with strict enforcement of public drinking laws, New York, has one of the lowest.

But many other cities with lax enforcement of public drinking laws have far lower rates of violent crime than New Orleans. Las Vegas had exactly the same murder rate as New York in 2012 (5.1 per 100,000 people), and Seattle's was even lower -- just 3.7 per 100,000 people. Moreover, some of the cities with the highest arrest rates for public drinking -- Cleveland and Chicago -- have unusually high rates of violent crime.

So the argument that issuing tickets for public drinking is surefire a way to reduce the rate of serious crimes is perhaps more tenuous than the Broken Windows advocates would like to believe. Indeed, most of the empirical research conducted on the Broken Windows theory has indicated that misdemeanor arrests have little or no correlation with reductions in violent crime -- correlation is not causation, after all.

Even in the absence of a national movement for repeal, though, some lawmakers have made small changes, in the expectation that public drinking could bring their cities more tourists than crime and misrule. Over the last decade, about a dozen cities, mostly in the heartland, have designated small sections of their downtowns as "Entertainment Districts" where tourists and locals are permitted to drink alcoholic beverages in the streets. (Lincoln, Neb., became the latest in October, and a law currently being debated in the Ohio Senate could pave the way for such districts in Cleveland and Cincinnati.)

Salon's Henry Grabar argued, in a September essay on entertainment districts, that because these neighborhoods are subject to tight police control and are heavily commoditized, they're mere simulacra of free cities. Relegating public drinking to special, Disney-fied spheres of corporate control merely creates the illusion that the citizenry can be trusted to regulate its behavior.

Some opponents of public drinking might contend that they do not want their streets to look like Bourbon Street or the Las Vegas Strip. But one might also argue that those places became as riotous as they are in part because, in the last 40 years, public drinking was banned everywhere else, making them "America's playgrounds" by exclusion. If public drinking were again legal across the country, outdoor revelry would potentially diffuse out into the rest of the country and become as unremarkable as it was in the 1800s.

That's not to say that that the ideal system of control of public drinking is no control. Forgoing laws on public drinking can cause problems of its own. Butte, Mont., a mining town of 34,000 in between Bozeman and Missoula, was until recently one of the very few U.S. towns with no restrictions on public drinking whatsoever. The residents of Butte were proud of their rebellious status, and used it to attract tourists throughout the summer.

"We're the festival capital of Montana. The two biggest are the Evil Knievel Festival and the Montana Folk Festival. And it’s largely because of our drinking laws," Matt Vincent, the town's chief executive, told HuffPost.

Outside festival season, most of the people who take advantage of the lax approach to public drinking are college students and young professionals. They spill out of the bars in Butte's vibrant Uptown neighborhood clutching cocktails and smoking cigarettes late into the night. After last call at 2 a.m., they like to congregate around the 24-hour M&M diner, drinking cans of beer on the street until dawn. But they also have a propensity, especially on Friday and Saturday nights, for shouting, fighting and urinating on the sidewalk -- so much so that the Uptown residents started to get upset.

In the fall of 2012, they petitioned the city council to pass a law to ban public drinking between 2 a.m. and 8 a.m. A huge town debate ensued: The young and longtime Butte residents largely opposed the law, while it was supported by the local business owners and upper-middle-class gentrifiers who live in Uptown's new luxury lofts. The debate was exactly the type of heated, rich discussion that most of the rest of the country has never had. Two weeks before the city council was scheduled to vote, six members said they were in favor of it, and six looked like they opposed it.

"As chief executive, which is like our version of a mayor, I have the power to break a tie," Vincent said. "And I've done it before. But this seems like too delicate an issue for that to be appropriate. So if the vote really does end up six-six, I'm not going to intervene, and it will fail. That way, we can have a town referendum on it, and every voice can be heard."

In the end, it didn't come to that. At the eleventh hour, Town Commissioner Sheryl Ralph decided to vote for the bill, ensuring its passage.

"Although I still don't agree with the ordinance myself, it is now clear that ... in my district there is a clear majority of people who favor the ordinance and I will respect their wishes," she told the Montana Standard.

At some point after Dec. 20, when the law takes effect, the Butte police will issue its first ticket (up to $500) for drinking in public. But the fine will come after a robust debate by the town, and not as a knee-jerk reaction to the loss of an old tool favored by the state.

And besides, Butte residents will still be able to drink in public with impunity 18 hours of the day, 365 days a year.

A group of men stand with beer glasses and a bottle of wine outside Petryl's Saloon at 125 W. 19th Street in Chicago, late 19th Century.

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/12/14/public-drinking-laws_n_4312523.html

12/14/2013 07:32 am ET | Updated Jun 26, 2015

- Joe SatranStaff Writer

AP

New Year's Eve was still three weeks away, but by dusk, crowds had thronged Times Square. Everyone's eyes were trained on the screen on 42nd Street. The buzz of mass anticipation hung in the air. Suddenly, the lights on the screen flickered with the message everyone had been waiting for: "Utah is voting!" A hush fell across the crowd. The "yes" votes from Pennsylvania and Ohio had come in hours earlier, so if Utah voters approved the 21st Amendment as well, liquor would become legal for the first time in the United States in 14 years.

At 5:33 p.m., the screen changed again. "Prohibition is dead!" it declared. Times Square erupted in cheers. The good news rippled out through the city, shouted from the mouths of paperboys and in triumphal booms from the ships in the harbor. That night, all across America, people celebrated by crowding into former speakeasies, hosting raucous parties and drinking in the streets.

Customers buying beer at a makeshift bar in the streets of Chicago, after the legalization of alcohol on Nov. 10, 1933. (Photo by FPG/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

This month, 80 years later, some Americans celebrated the anniversary of the Repeal with old-timey cocktails, good craft beer or at least a festive hashtag (#RepealDay!). But there wasn't much drinking in the streets. Because America is in the grip of a new Prohibition: One that makes it illegal to drink alcohol in public.

Hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of people are arrested or ticketed for drinking in public every year. Millions of others refrain from doing so because they have been conditioned to believe that public drinking is an act as obviously illegal as shoplifting or nude sunbathing in a city park -- even though it was perfectly legal nearly everywhere in the world as recently as 1975.

This Prohibition, unlike the last, isn't the result of a constitutional amendment. Nor did it emerge overnight. The net of laws that now bans public drinking across most of the country took state and city lawmakers 40 years to weave. Most of these laws attracted as little public notice upon their passage as any other state or municipal law, which has allowed this net to be lowered so slowly and quietly that many people don't realize that anything has changed.

Another difference between this Prohibition and the one that ended 80 years ago? Many of the people who are aware of this one actually like it. They say that the virtually nationwide ban on public drinking has "cleaned up the streets," reduced per capita alcohol consumption and even helped slash the incidence of serious crimes such as murder and arson.

They may have a point. But it's also likely that they underestimate the price we pay for the benefits of this Prohibition. Decades of evidence suggest that laws against public drinking are enforced unequally and capriciously, disproportionately hurting the most downtrodden members of society. More fundamentally, these laws allow the state to interfere with individual behavior to prevent an act that in itself harms no one.

AN INTRICATE PATCHWORK

Whether the national prohibition on public drinking is good or bad, it's certainly confusing. Laws against drinking in public places -- streets, sidewalks, parks, beaches, stadiums -- vary wildly from state to state, city to city and in some places, from block to block.

Public drinking is now punishable by fine or jail time across the vast majority of the country. Seventeen states ban it completely. It's also illegal in 89 of the 100 most populous cities in the country, including the top 10. The map below illustrates the bewildering patchwork of public drinking laws currently in effect across the U.S.:

But this map actually masks the true extent of the confusion, because the various municipal and state statutes banning the behavior define the offense in myriad ways. They also stipulate a huge range of penalties for offenders, from a simple fine of $25, payable by mail (New York City), to a ticket of up to $1,000 or a jail sentence of up to 6 months (Hawaii and New Mexico).

What's more, enforcement of public drinking statutes seems to vary widely from one place to the next. Police departments and municipal courts in several major U.S. cities provided data on enforcement to The Huffington Post, which reveal huge gaps in the arrest rate among comparable cities, as the chart to the right illustrates.

(To some extent, the chart may reflect actual differences in the frequency with which city residents drink in public. For example, people who live in pedestrian-friendly cities like Chicago or New York may have more occasion to drink in public than those who live in cities like Tucson, Ariz., or Austin, Texas. Yet it also seems unlikely that New York City residents drink in public at rate 20 times that of the residents of Philadelphia or Seattle, so differences in how the laws are enforced likely account for the significant disparities.)

HuffPost's analysis could only positively identify 20 towns or cities of any size in which drinking is legal in some, if not all, public places. About half of these cities allow public drinking only in specially designated "Entertainment Districts" that have been established in the past few years in the hopes of attracting booze-loving tourists.

The cities that do allow drinking in public don't have as much in common as one might think. Cities as varied as New Orleans and Butte, Mont., Las Vegas and Savannah, Ga., allow residents and tourists alike to drink in the streets and parks.

But to ask how these places were independently able to legalize public drinking is to fundamentally misunderstand the situation. Towns like New Orleans and Butte didn't have to take specific steps to allow public drinking -- they just never banned it.

About 6 million people -- just under 2 percent of the country -- live in a municipality that allows some measure of public drinking. Even if one rounds up, that leaves 97 percent of Americans facing a ticket or jail time if they step outside their homes while carrying a glass of Chardonnay.

That would have shocked our Founding Fathers -- and even possibly our great-grandfathers. Alcohol has been regulated in North America since at least the earliest days as British colonies. But until the middle of the 20th century, there were exactly two types of American alcohol law: regulations of its sale and bans on public drunkenness. Neither sought to control drinking directly.

Sound legal and philosophical arguments distinguished the laws against the act of drinking from those on the sale of alcohol or public drunkenness. The great legal minds of the 19th Century generally believed that laws should only regulate social activities, or conduct involving multiple parties. The philosopher John Stuart Mill, for example, argued, in his famous essay "On Liberty":

Whenever, in short, there is a definite damage, or a definite risk of damage, either to an individual or to the public, the case is taken out of the province of liberty, and placed in that of morality or law.

But with regard to the merely contingent, or, as it may be called, constructive injury which a person causes to society, by conduct which neither violates any specific duty to the public, nor occasions perceptible hurt to any assignable individual except himself; the inconvenience is one which society can afford to bear, for the sake of the greater good of human freedom.

Anathema to this school of thought are laws that would prevent calm, relatively sober people from drinking wherever they like. So no such laws were passed.

A combination of Victorian social mores and a scarcity of disposable drinking vessels kept most Americans from partaking in their legal right to drink in public too often. But public drinking was certainly a feature of everyday life. Miners and laborers on their lunch hour would pay women and children to bring them buckets of draught beer from local saloons for open-air consumption, a practice known as "rushing the growler."

Oil rig workers in Bayonne, N.J., "rush the growler" on their lunch hour in 1909.

In one newspaper article in 1868, Mark Twain dismissed New England as "the land of steady habits" because he noted so few people drinking and smoking in the streets. And across the country, outdoor festivals for events like New Year's Eve, St. Patrick's Day, major political or military victories and the American centennial always featured alcohol. The relative dearth of written evidence of public drinking may be a sign of how normal it was: Writers may not have thought to comment on it.

It took Prohibition to shatter the assumption that a person could drink with impunity wherever he or she liked.

The Volstead Act, the sweeping 1919 federal law that enforced Prohibition, specifically banned the carrying of containers of alcohol in the street, among other things. The nominal justification for this measure was that carrying wine or bourbon down the street was assumed to be evidence of intent to sell. So the measure was still, at its heart, a regulation of sales. But it effectively confined drinking to speakeasies and private homes.

On the other hand, the repeal of Prohibition 80 years ago gave the states a chance to write wholly new alcohol laws, but they did not use the opportunity to ban public drinking.

Some states essentially restored the legal regime that had been in place prior to 1918. Many others looked to "Toward Liquor Control," a report commissioned by former teetotaler John D. Rockefeller Jr., written by attorney Raymond Fosdick and engineer Albert Scott, that suggested specific laws based on best practices in other countries. Nowhere in the 300 pages of the report do Fosdick and Scott mention the idea of banning the act of drinking in public outright. And the historical record suggests that, for two decades after Prohibition, no one else did, either.

THE BIRTH OF CONTROL

But 20 years and seven days after the repeal of the 18th Amendment, Chicago Alderman Harry L. Sain, who represented the city's 27th Ward, approached his fellow aldermen with a problem.

Shasta Dam construction workers drinking beer at entrance to bar in Central Valley, Calif., c. 1940.

He said he was hearing more and more reports of "bottle gangs" -- groups of indigent men who would stand on sidewalks sharing bottles of liquor -- plaguing the Skid Row of his district, and littering the streets with empty wine bottles and beer cans. Chicago police officers could arrest rowdy individuals using the city's broadly defined ban on "disorderly conduct," but Sain wanted them to be able to break up the bottle gangs before they got rowdy.

His solution? A law that would prohibit "drinking in the public way," namely city streets, parks, vacant lots and any other place open to public view. Violators were subject to a $200 fine, the equivalent of about $1,750 in today's money. On Dec. 12, 1953, the law passed handily. One of Sain's fellow aldermen, Mathias Bowler, told the Chicago Tribune the new law was "good news for [his] ward too," noting that he'd heard that "five fellows die[d] there drinking out of bottles on the street."

If Chicago was the venue where public drinking laws made their debut, Newport, R.I., was where they hit the big time.

Over July 4th weekend 1960, the traditional summer resort for the East Coast elite was the scene of a notorious drunken riot. The town was hosting one of the most important jazz festivals in the country for its sixth summer. But after a popular 1959 documentary about the festival raised the event's profile, 12,000 teens showed up hoping to see Louis Armstrong, Dizzy Gillespie and Dinah Washington perform, only to find it sold out.

While loitering outside the concert, they started drinking. Then they got angry.

About 2,000 of them charged the gates of the festival. Newport police tried to hold them back, but the crowd started throwing beer cans and wine bottles. The police called in the National Guard, which dispersed the crowd with tear gas. It was a disaster.

The following year, Newport regrouped, revising its criminal code to better accommodate the festival. One of the key changes, as the Boston Globe put it, was that a "special ordinance bans drinking in public." The reforms worked, and subsequent festivals went off without a hitch.

The success of the Newport law inspired other towns across the country that were struggling to control large groups of rowdy, drunken teens -- in particular the Florida towns to which college students started flocking for Spring Break after the release of movies like "Gidget" and "Where The Boys Are." Fort Myers, Jacksonville, Miami, Daytona Beach and Hialeah all passed restrictions on public drinking between 1964 and 1970, years before most other towns in America did.

On the whole, though, adoption of public drinking laws was lackadaisical. Until about 1975, such laws were so rare that every newspaper article describing a new one explained it as if it were completely novel. And they might have remained that way forever -- if the Supreme Court hadn't intervened.

DRUNKENNESS DECRIMINALIZED

In 1963, it was unlikely that you would have been arrested for drinking in public -- but you could have been arrested for being a "common drunkard."

Most states and municipalities had laws on the books that made it illegal to be a "common drunkard" or a "vagrant," terms used to describe those who would be known today as alcoholic and homeless, respectively. The police arrested hundreds of thousands of people every year for violating these so-called vagrancy and public drunkenness laws, which were at the heart of the police's mission to control urban social disorder. Such laws defined life on Skid Row: Some perennially homeless, alcoholic men spent years of their lives in jail, in 30-day increments, on charges of public drunkenness and vagrancy.

Two painters sit on a sidewalk during a break, drinking beer and eating sandwiches, c. 1945. (Photo by Harold M. Lambert/Lambert/Getty Images)

But in the late '50s and early '60s, legal scholars started to criticize how these laws were enforced, using arguments that would be familiar to anyone following the contemporary debate around drug decriminalization. Critics argued that arresting, charging and incarcerating "drunkards" wasted scarce police and court resources; that the laws were enforced more stringently against poor black people than against affluent white people; and that "public drunkenness" was a moral and medical issue better addressed in churches and hospitals than jails and courtrooms.

In short, they called for reform. The Supreme Court heeded that call in 1964, in its landmark decision Robinson v. California. The immediate effect of the decision was to strike down a California statute classifying drug addiction as a crime. But it also rang the death knell for all "status offenses," vagrancy chief among them.

In a later decision, the Supreme Court chose not to strike down public drunkenness laws as unconstitutional. The court found that such laws prohibited the act of "appearing in public while drunk," rather than "being an alcoholic."

But the writing was on the wall. Vaguely defined status offenses like public drunkenness and vagrancy were constitutionally unsound and, in the long run, unenforceable.

Further pressure to overturn public drunkenness laws came from the executive and legislative branches. Two Presidential Commissions on Crime described public drunkenness laws as ineffective deterrents to repeat offenders and a burden on the criminal justice system. They strongly recommended that public drunkenness be decriminalized. And in 1971, Congress passed the Uniform Alcoholism Treatment Act, which called on states to decriminalize public drunkenness and shift their handling of public inebriates to the health system. Thirty-five states adopted it, and most of the others passed similar laws.

By the end of the '70s, arrests for public drunkenness had dropped by half nationwide. (They would continue to fall, almost unabated, until the present.) The era of criminalized public drunkenness was over, after 350 years. Doctors and advocates for the rights of the homeless and alcoholics started to breathe easier.

Not everyone was happy, though. Entrenched business interests and well-to-do citizens, and their allies in state and local legislatures, still wanted the police to take undesirable homeless and alcoholic people off the streets. But as public drunkenness and vagrancy were no longer criminal acts, the police had no tools at their disposal.

Enter the ban on public drinking.

CITIES EMBRACE THE NEW PROHIBITION

The idea of implementing a ban on public drinking as a substitute for a ban on public drunkenness isn't as obvious as it might seem.

True, "drinking in public" sounds a lot like "drunk in public" -- so much so that, to this day, many people conflate or confuse the two types of law. While both regulate the overlap of alcoholic beverages and public space, they address fundamentally different behaviors.

A ban on public drunkenness punish the odious outcomes of excessive drinking. It divides the landscape of public social conduct into two large zones -- sober and drunk, good and bad -- and tells people they will be punished if their behavior passes from the sober zone into the drunk zone. It establishes a subjective moral standard for each individual to uphold in his or her own way.

Delivering liquor the day after the repeal of Prohibition, driver Tony Pasquale takes a drink in Manhattan. (Photo By: Ed Jackson/NY Daily News via Getty Images)

Public drinking laws, on the other hand, ban one specific type of action: drinking an alcoholic beverage in a public place. They leave no room for ambiguity or subjectivity. You either are violating the law, or you aren't.

A debate on the merits of these two types of law could raise important ethical and moral questions about police discretion, the impartiality of justice and our basic concept of public space.

But lawmakers and police chiefs made a much simpler calculation when they started to embrace the public drinking law in the wake of decriminalization of drunkenness. Its specificity and lack of ambiguity made it much easier to defend in court than charges of public drunkenness or vagrancy. And it could still be easily used to arrest homeless people and alcoholics. Homeless people often can't afford to drink in bars, and they don't necessarily have a place to drink in private. If they want to drink, they're almost bound to commit the crime of drinking in public.

Between 1975 and 1990, in the wake of the decriminalization of public drunkenness and vagrancy, cities and states gradually imposed bans on drinking in public.

New York City Council voted to ban public drinking just six weeks after public drunkenness was decriminalized throughout New York state on Jan. 1, 1976. Mayor Abraham Beame vetoed the bill, citing its "disturbing civil-liberties implications." Three years later, the council passed another ban, despite vociferous opposition from minority groups -- and Mayor Ed Koch signed it into law.

In May 1983, the Supreme Court struck down California's vagrancy law for being unduly subjective. During the Supreme Court hearing, California Attorney General George Deukmejian said that eliminating the vagrancy law ''effectively removed an arrow from the quiver of the police at a time when all proper weapons are required to deter criminal activity." By August, the City Council was considering a ban on public drinking at the request of the police department. That November, the LAPD got a brand new arrow.

Tim Riggins and Tyra Collette, two of the characters on "Friday Night Lights," enjoy beers in a West Texas field near the fictional town of Dillon.

At some point, though, public drinking bans simply became common enough that even cities without a pressing need for such laws felt pressure to pass them. In 1990, for example, when Irvine, Calif., passed its ban, the city's community services superintendent noted to the LA Times that "You can't consume alcoholic beverages in public" in almost any other city in Orange County, but "you can in Irvine."

The last big holdouts were the Texas giants: Houston, Dallas, San Antonio and Austin. They were prevented from joining in the banning bonanza of the '80s by a state law that prevented cities from passing any law that regulated alcohol consumption. But they clearly felt left out, because they pressured the state to change. They won in 1993.

By 1995, the bulk of the cities in the U.S. had passed bans on public drinking. Since then, these laws have even started to proliferate abroad, especially in the U.K. and Australia. Dublin, Ireland, outlawed public drinking in 2008. Even Prague, long Europe's premier destination for drunken revelry,moved to ban drinking in the streets this fall.

Public drinking bans may be America's most successful culinary export since the Big Mac.

CRIME AND PUNISHMENT

Of course, laws alone do not a Prohibition make. Enforcement must be consistent and harsh enough to make reasonable people believe they're likely to be punished if they break the law. So long as the police used public drinking laws as a tool primarily against homeless alcoholics and mobs of drunken teenagers, the country remained a crucial leap away from an outright Prohibition.

The final piece of the puzzle came during the '90s, as police departments in cities from Seattle to New York began to embrace the "Broken Windows" philosophy of enforcement. The idea holds that strict enforcement of minor "public order" infractions can revive downtrodden neighborhoods, eventually reducing more serious crimes like murder and arson. Advocates of the Broken Windows theory emphasized the enforcement of public drinking laws as early as 1982, when the Atlantic Monthly published the article from which the movement takes its name.

In one pivotal passage, authors George Kelling and James Wilson write:

People start drinking in front of the grocery; in time, an inebriate slumps to the sidewalk and is allowed to sleep it off. Pedestrians are approached by panhandlers. [...] Such an area is vulnerable to criminal invasion. Though it is not inevitable, it is more likely that here, rather than in places where people are confident they can regulate public behavior by informal controls, drugs will change hands, prostitutes will solicit, and cars will be stripped.

Whether or not Kelling and Wilson assume here that public drinking is, strictly speaking, illegal -- it's an open question -- the message is clear: Public drinking is bad for communities. So bad, in fact, that the police should target it specifically as an easy way to reduce rates of more serious crimes.

Which is exactly what police forces did throughout the '90s. Enforcement rates of public drinking laws skyrocketed, inculcating the idea that public drinking is a crime no matter who does it.

Yet patterns of police enforcement of public drinking laws do suggest their origin as a replacement for unacceptably vague and discriminatory status offenses. Though national data on public drinking infractions are hard to come by (or nonexistent), the few studies of police enforcement indicate that poor, black people are arrested at rates many times higher than affluent white people.

Judge Noach Dear of Brooklyn had his staff look into tickets for the offense in his borough in 2012, and found that "More than 85 percent of the 'open container' summonses were given to Blacks and Latinos. Only 4 percent were issued to whites." Nearly 40 percent of Brooklyn residents are white.

In 2001, the City of New Orleans commissioned a study of a then-30-year-old city law that banned open glass and metal (but not plastic) drinking containers on the streets. Researchers found that nearly 80 percent of those charged with violating the open container law were black, prompting the city council to repeal the ban.

That's all to say that anyone can be ticketed for drinking in public under the terms of the new Prohibition. Just as anyone couldbe ticketed or jailed for public drunkenness in 1960. But the available research suggests that young black kids drinking 40s on the corner are more likely to be ticketed than a prosperous, middle-aged white couple drinking a bottle of wine in the park.

A NEW REPEAL MOVEMENT?

The new Prohibition arrived, then, both quickly and slowly. Most cities passed their laws against drinking in public relatively quietly, without much debate in city councils or input from the general public. But the country passed the laws over a long enough span of time that the connection between the old status offenses and the new public drinking bans never became readily apparent to most observers. No one has ever written a scholarly article on the emergence of public drinking laws in America, for example.

The nation certainly seems to have accepted this new Prohibition without resistance.

A previous national poll, conducted in 2000 -- and the only one this reporter found on the subject -- indicated overwhelming public support for restrictions on public alcohol consumption: 92 percent of respondents said they favored laws against drinking in the streets and on sidewalks; 86 percent said they favored restrictions on drinking in parks and beaches; and 81.4 percent said they favored restrictions on drinking in stadiums and concerts. Support for public drinking bans in that poll was much higher among older people, women, ethnic minorities and those from low-income households than among young people, men, whites and those from high-income households.

To see whether attitudes had changed in the last 13 years, HuffPost conducted its own poll on the issue with our partners at YouGov. The wording of the questions differed slightly from those of the 2000 poll, and was conducted online rather than over the phone, so the two aren't directly comparable. While HuffPost/YouGov's results revealed many of the same relative differences in support across demographic categories and with regard to specific sites for public drinking, the new poll found much higher levels of support for the legalization of public drinking across the board than the previous poll did.

The infographic below illustrates the top-line results:

The HuffPost/YouGov poll was conducted Dec. 2-3 among 1,000 U.S. adults using a sample selected from YouGov's opt-in online panel to match the demographics and other characteristics of the adult U.S. population. Factors considered include age, race, gender, education, employment, income, marital status, number of children, voter registration, time and location of Internet access, interest in politics, religion and church attendance.

Even in the more recent poll, though, those in favor of restricting street drinking outnumber those in favor of legalization 2-to-1, which is hardly the makings of a latter-day repeal movement.

Some of the ban's popularity may stem from a belief that cracking down on public drinking in the '90s also slashed national crime rates. Police started enforcing public drinking bans aggressively just as rates of serious crime started to plummet in many major cities across the country. Government officials who pushed the Broken Windows theory most forcefully often argued that public drinking arrests have been a crucial factor in that decline. They also note that the city most closely associated with street drinking is New Orleans, which has one of the highest murder rates in the country; while the city most closely associated with strict enforcement of public drinking laws, New York, has one of the lowest.

But many other cities with lax enforcement of public drinking laws have far lower rates of violent crime than New Orleans. Las Vegas had exactly the same murder rate as New York in 2012 (5.1 per 100,000 people), and Seattle's was even lower -- just 3.7 per 100,000 people. Moreover, some of the cities with the highest arrest rates for public drinking -- Cleveland and Chicago -- have unusually high rates of violent crime.

So the argument that issuing tickets for public drinking is surefire a way to reduce the rate of serious crimes is perhaps more tenuous than the Broken Windows advocates would like to believe. Indeed, most of the empirical research conducted on the Broken Windows theory has indicated that misdemeanor arrests have little or no correlation with reductions in violent crime -- correlation is not causation, after all.

Even in the absence of a national movement for repeal, though, some lawmakers have made small changes, in the expectation that public drinking could bring their cities more tourists than crime and misrule. Over the last decade, about a dozen cities, mostly in the heartland, have designated small sections of their downtowns as "Entertainment Districts" where tourists and locals are permitted to drink alcoholic beverages in the streets. (Lincoln, Neb., became the latest in October, and a law currently being debated in the Ohio Senate could pave the way for such districts in Cleveland and Cincinnati.)

Salon's Henry Grabar argued, in a September essay on entertainment districts, that because these neighborhoods are subject to tight police control and are heavily commoditized, they're mere simulacra of free cities. Relegating public drinking to special, Disney-fied spheres of corporate control merely creates the illusion that the citizenry can be trusted to regulate its behavior.

Some opponents of public drinking might contend that they do not want their streets to look like Bourbon Street or the Las Vegas Strip. But one might also argue that those places became as riotous as they are in part because, in the last 40 years, public drinking was banned everywhere else, making them "America's playgrounds" by exclusion. If public drinking were again legal across the country, outdoor revelry would potentially diffuse out into the rest of the country and become as unremarkable as it was in the 1800s.

That's not to say that that the ideal system of control of public drinking is no control. Forgoing laws on public drinking can cause problems of its own. Butte, Mont., a mining town of 34,000 in between Bozeman and Missoula, was until recently one of the very few U.S. towns with no restrictions on public drinking whatsoever. The residents of Butte were proud of their rebellious status, and used it to attract tourists throughout the summer.

"We're the festival capital of Montana. The two biggest are the Evil Knievel Festival and the Montana Folk Festival. And it’s largely because of our drinking laws," Matt Vincent, the town's chief executive, told HuffPost.

Outside festival season, most of the people who take advantage of the lax approach to public drinking are college students and young professionals. They spill out of the bars in Butte's vibrant Uptown neighborhood clutching cocktails and smoking cigarettes late into the night. After last call at 2 a.m., they like to congregate around the 24-hour M&M diner, drinking cans of beer on the street until dawn. But they also have a propensity, especially on Friday and Saturday nights, for shouting, fighting and urinating on the sidewalk -- so much so that the Uptown residents started to get upset.

In the fall of 2012, they petitioned the city council to pass a law to ban public drinking between 2 a.m. and 8 a.m. A huge town debate ensued: The young and longtime Butte residents largely opposed the law, while it was supported by the local business owners and upper-middle-class gentrifiers who live in Uptown's new luxury lofts. The debate was exactly the type of heated, rich discussion that most of the rest of the country has never had. Two weeks before the city council was scheduled to vote, six members said they were in favor of it, and six looked like they opposed it.

"As chief executive, which is like our version of a mayor, I have the power to break a tie," Vincent said. "And I've done it before. But this seems like too delicate an issue for that to be appropriate. So if the vote really does end up six-six, I'm not going to intervene, and it will fail. That way, we can have a town referendum on it, and every voice can be heard."

In the end, it didn't come to that. At the eleventh hour, Town Commissioner Sheryl Ralph decided to vote for the bill, ensuring its passage.

"Although I still don't agree with the ordinance myself, it is now clear that ... in my district there is a clear majority of people who favor the ordinance and I will respect their wishes," she told the Montana Standard.

At some point after Dec. 20, when the law takes effect, the Butte police will issue its first ticket (up to $500) for drinking in public. But the fine will come after a robust debate by the town, and not as a knee-jerk reaction to the loss of an old tool favored by the state.

And besides, Butte residents will still be able to drink in public with impunity 18 hours of the day, 365 days a year.

A group of men stand with beer glasses and a bottle of wine outside Petryl's Saloon at 125 W. 19th Street in Chicago, late 19th Century.

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/12/14/public-drinking-laws_n_4312523.html